How to overcome organisational silos

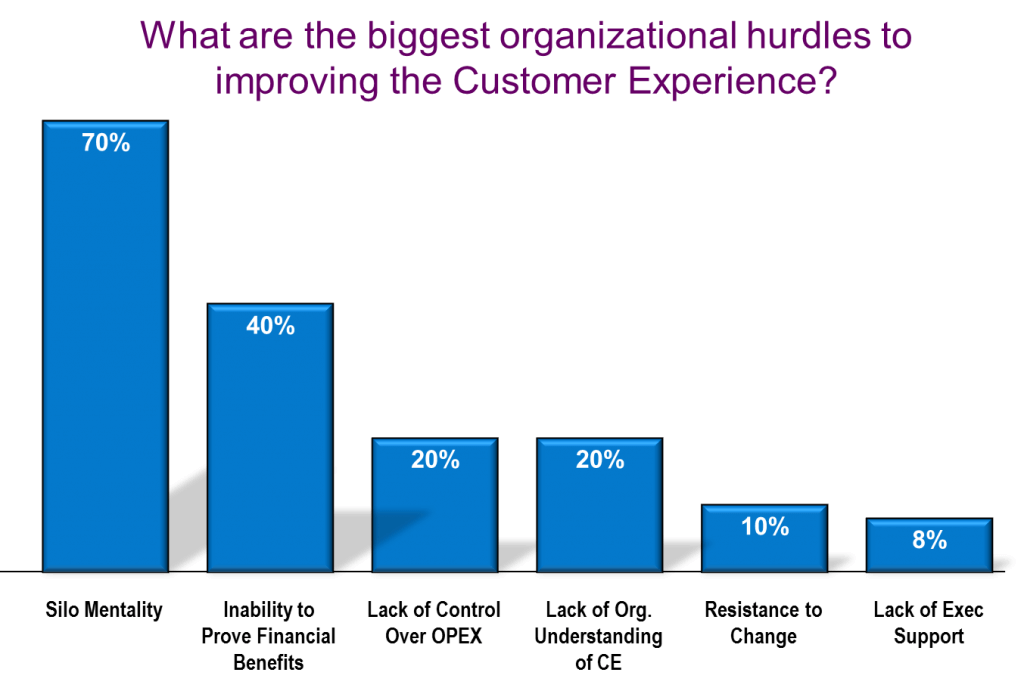

Have you got problems finding a common language and cooperation from people around the organisation for customer experience initiatives? Aren’t people usually supportive on words … until you actually ask them to do something? Research we did in 2012 amongst customer experience professionals and executives showed that “silo mentality” is the biggest organisational hurdle to improving the Customer Experience. This is understandable as the end to end Customer Experience touches many parts of the organization and as Tom Peters once said “any organisation over five people is too big”. You must have also heard of Jeff Bezos’ 2 pizza team rule i.e. that each team should be small enough to be fed by 2 pizzas.

Common sense says that people within the organisation should be working towards the same goal but reality is different.

As an article in Fast Company says:

Human nature forces people to want to do the best they can within their own ‘sandbox’ at the expense of everybody else. ‘Owning’ a function or a part of a business naturally brings forth a manager’s entrepreneurial spirit, and you don’t get to be head of a silo without being competitive. Managers rationalize their lack of cooperation as ‘I’ve been given this area to run as I see fit … “

Human nature forces people to want to do the best they can within their own ‘sandbox’ at the expense of everybody else. ‘Owning’ a function or a part of a business naturally brings forth a manager’s entrepreneurial spirit, and you don’t get to be head of a silo without being competitive. Managers rationalize their lack of cooperation as ‘I’ve been given this area to run as I see fit … “

The result of this thinking is bad enough when it is kept within a company, but when it spills over into customer relationships it can be disastrous.

Consequences

John Kotter points in a Forbes blog some of the consequences of the organisational silos. They:

- Destroy trust. Without trust there can’t be teamwork across an organization, and without a team that moves quickly, organizations fall behind their competitors.

- Cut off communications. It’s important to note as well that silos could be vertical or horizontal. Individual units can have high barriers between them or senior leadership can be completely isolated from lower management levels. Once your communication lines are cut off you don’t hear crucial feedback about customer or employee sentiments, competitors etc.

- Foster Complacency: In an organization where people in different divisions have little contact with one another, it’s easy to become inwardly focused and complacent with the status quo. It will cause them to miss new opportunities and hazards coming from competitors or customers and changes in the regulatory environment.

Breaking down organisational silos

Colin Shaw, founder & CEO of Beyond Philosophy, having spent 18 years working at BT (formerly British Telecom) and experienced first-hand the reality of company politics and silos as well as having worked with a number of blue chips on their customer experience transformation programs points in his blog that one of the ways to address the silo mentality problem is by establishing Customer Experience (CE) Council. The idea of the CE Council is to:

- Bring together all departments who impact the Customer Experience. It should enrol the key players so those left out cannot block a change and also show credibility and commitment of senior leadership to the rest of the organisation

- Ensure everyone understands the inter-dependencies between departments and the effect on the customers experience

- Work as a team to improve the end to end Customer Experience

This is what John Kotter would call a “guiding coalition”. And it’s proven in practice.

One of our clients, Maersk Line (one of the world’s largest container shipping companies with operations in 125 countries) at our recommendation gave regional divisions the option of putting regional Customer Experience Councils in place. The 55 regions that have set up local councils also received a three-day training course in customer experience improvement methods. The firm then did a study comparing regions with and without a council. The result: participating local offices score 10 points higher on their NPS® than those offices that opted out. The Customer Experience Councils have been just one part of an overall customer experience program that led to a 40% rise of Maersk Line’s Net Promoter Score® and prompted Forrester to do a case study on them. You can also read our case study here.

The other two advises that John Kotter gives in his blog are:

- Bring the outside in: Make divisions share data with one another so people understand how each division is performing, what customer or external stakeholder complaints are, and where there is room for improvement.

- Focus on opportunity, not crisis: While crisis can be a catalyst for action, fear also can send people running for the door. Help people in different divisions understand how they have a chance to make the organization better and more powerful by eliminating the barriers between divisions or management levels.

These are all good advices that will help you address the silo mentality and the reason I listed them here was to bring in some of the best advice out there in one place. However I think there is something missing. Even if key people are gathered in one team to look at the end to end customer experience and the teams share feedback etc. and look at the positive side of things rather than blaming each other, if people are coming from their own perspectives about what’s the right thing to do for the customer you’ll find yourself in endless and fruitless discussions. And the result would still be the same – inconsistent and unremarkable experience. And as Robert Stephens, founder of the Geek Squad says “Marketing is the price you pay for being unremarkable”.

What is necessary is to define what will be the key focus of the company and what it should be renowned for e.g. how should the intended customer experience look and feel like. Unless you do that there won’t be enough of a common ground to smash the silo thinking and deliver a consistent and deliberate customer experience.

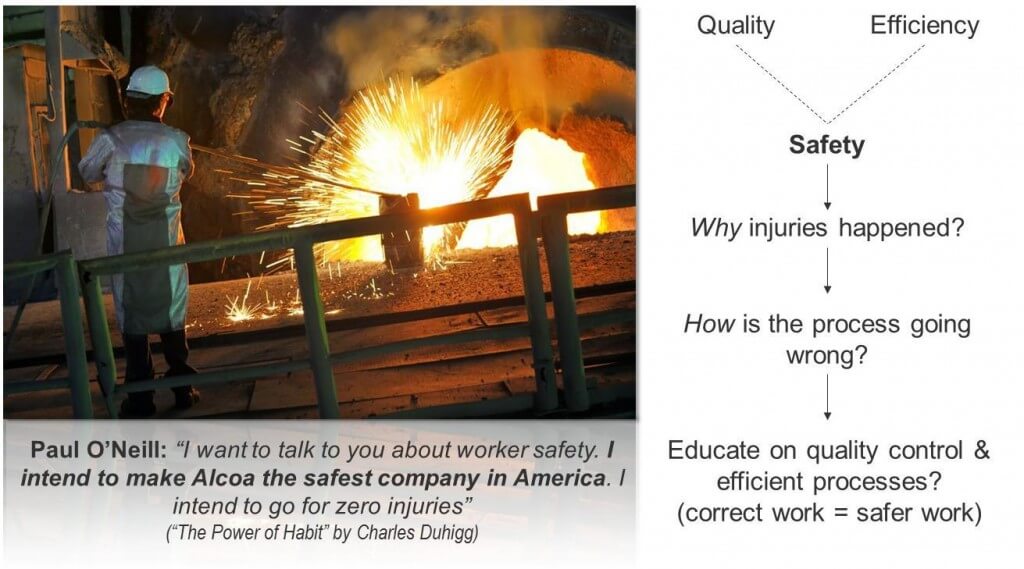

Take for example the way Paul O’Neill made the turnaround in Alcoa (the biggest aluminium producer in the US, manufacturing everything from the metal for the Coca Cola cans to bolts that hold satellites) as presented in Charles Duhigg’s book “The Power of Habit”. In the mid 80’s the company had a problem with efficiency and the quality of the products. The previous CEO had tried to mandate improvements and 15 000 workers had gone on strike. As the author says in a company as old you can’t just flip a switch and expect everyone to work harder or produce more. So Paul O’Neill figured out if he wanted the organisation to change he needed to focus on something that everybody –unions and executives – could agree was important. He needed a focus that would bring people together, that would give him leverage to change how people communicated and worked.

So he decided to focus on safety as everyone, he thought, deserves to leave work safely, without being scared that feeding your family will kill you. When has visited a plant he told workers “I’m happy to negotiate with you on anything but safety”. The beauty of course was that no one would argue against safety. What most people didn’t realise though was that improving on safety entailed the most radical realignment in Alcoa’s history. For to improve on “safety”, you need to understand why injuries happen. To understand why injuries happen, you need to understand how the manufacturing process is going wrong. To understand how is the process going wrong you need to educate employees about quality control and process efficiency, because correct work is also safer work.

As we mentioned above one of the consequences of silos are the cut off communication lines. In the case of Alcoa, when they decided to focus on safety the CEO asked, in the event of an injury, to be contacted by the business unit (BU) president within 24 hours and be ready with a recommendation of how to avoid such accident in future. For the BUs’ presidents to be able to do that, they needed to hear from their VPs as soon as an accident happened. The VPs on their side had to be in constant communication with floor managers, who in their turn asked workers to raise warnings if they saw a potential problem and keep a list of suggestions nearby.

Communication improved across the different plants and countries as well. O’Neil asked everyone to log in to their network when they arrived at work (this was not common at all in the late 80’s) so they can share safety information. Soon people started to talk and share not just safety concerns but also market intelligence, trends and ideas.

Another common problem with silos is that everyone is looking at things from their own siloed perspective and is there to protect their department, which makes it difficult to find common ground to solve a problem in the way that’s best for the organisation as a whole in the long term. Focusing in this common goal “safety” allowed Alcoa to create a common language. Rules that unions had opposed for decades – such as measuring productivity of individual workers – were suddenly embraced, because such measurements helped everyone figure out where the manufacturing process was defecting and posed safety hazards. Similarly policies that managers had long resisted – such as giving workers autonomy to shut down a production line when the speed became overwhelming – were now welcomed because that was the best way to stop injuries before they occurred.

Do some of these problems sound familiar to you? Think again! In the late 80’s and 90’s the push was for efficiency and in some cases it led to a run to the bottom cutting costs to the bone. Then some recognised that this is not sustainable platform for competition. Facing the prospect of death by efficiency they moved on the path of customer experience. Autonomy to shut down the production line equals employee empowerment nowadays and is still a hot topic to discuss for many organisations we have worked with.

The approach of Alcoa would still be considered pretty advanced even today as improving the quality of the products means better customer experience as well and overcoming the silos means more engaged workforce, which is linked with improving the organisational performance and experience as well. People took the safety thinking on board to such an extent that when they saw workers on the street or on another site working in a way that poses safety hazard to them or the people around they went to make them a remark and teach them of the importance of quality control.

What Alcoa found is that when they tackled safety problems it also led to other benefits. For example when molten metal was splashing and injuring workers they redesigned the pouring system which resulted in less raw material wastage. When a machine kept breaking down posing hazard to employee safety they replaced the machine, which resulted in higher quality products as they found out that malfunctioning equipment was the biggest cause for poor products.

All this had tangible performance benefits as you could imagine. By the time Paul O’Neil retired in 2000 the company’s net income and the value of the stock had risen 5 times.

A recent report by the CFI Group found that customer satisfaction leads to higher stock prices so maybe it’s time for your management to define what your customer experience should look like. Take pictures and document their commitment to it and then use it as a guiding light to start overcoming those silos.

| Zhecho Dobrev is a consultant and project manager for Beyond Philosophy. He has worked with a wide array of large corporate companies. Zhecho’s expertise includes customer behaviour analytics, customer loyalty, complaints management and journey mapping. He holds an MBA and Master’s degree in International Relations. Zhecho Dobrev on Twitter @Zhecho_BeyondP |